Maximizing Boycott Outcomes Through Analysis

By Eli Ibanga

Edited by Victoria Sosa

Boycotts are the best vehicle for change within the USA due to the reduced risk to participants. For these protests to realize their full potential, analysis should be done to identify the best targets, as well as increase collaboration between leftist, religious, and traditional liberal groups.

Rationale

The erosion of civil liberties in the United States has created a groundswell of activism. We’ve had several one-off days of protests, calls for organizations to divest from companies complicit with the Trump administration, plans for a National Day of Strike, complete and total boycott of all complicit companies, targeted boycotts, etc. While this is good, I suspect that the various overlapping protests and boycotts see net lower participation and impact than mobilizing all efforts to one decisive action. The planning of these events does not necessarily determine if the target is the most ideal, or if the protesting body is willing to participate. Consider the Target boycott from last year. This faith group-led boycott began because Target backed off from diversity initiatives around the time of the inauguration of the current Trump presidency. The boycott was somewhat effective, with the Target CEO declaring his resignation (only to become the Executive Chair of the Board). Perhaps the outcome could have been more favorable if business analysis was used in its planning and execution. This is by no means a knock against those who have been on the front lines. Instead, I’d like to consider the current state of affairs and what steps we can take as a nation to move the needle towards a free and fair society.

Objective - Stop ICE

Currently, ICE has been on a warpath for several months, violating civil and human rights of undocumented persons and US citizens on several occasions. As of writing this, they have murdered Alex Pretti in Minnesota. While community leaders across the nation have demanded that ICE be reined in, Trump and the DOJ have no such desire. Congress lacks the cohesion to do so, and in some cases are also not inclined to. But as many a business executive will tell you, change often begins in the private sector before it happens in government. This isn’t because US companies are altruistic, but rather they are beholden to the shareholder. Therefore, they prefer outcomes that maximize profit over morality. As consumers, it is our values coupled with how we spend our money that influences how these companies behave. We can stop ICE overreach through targeted leveraging of our collective spending power.

Methodology

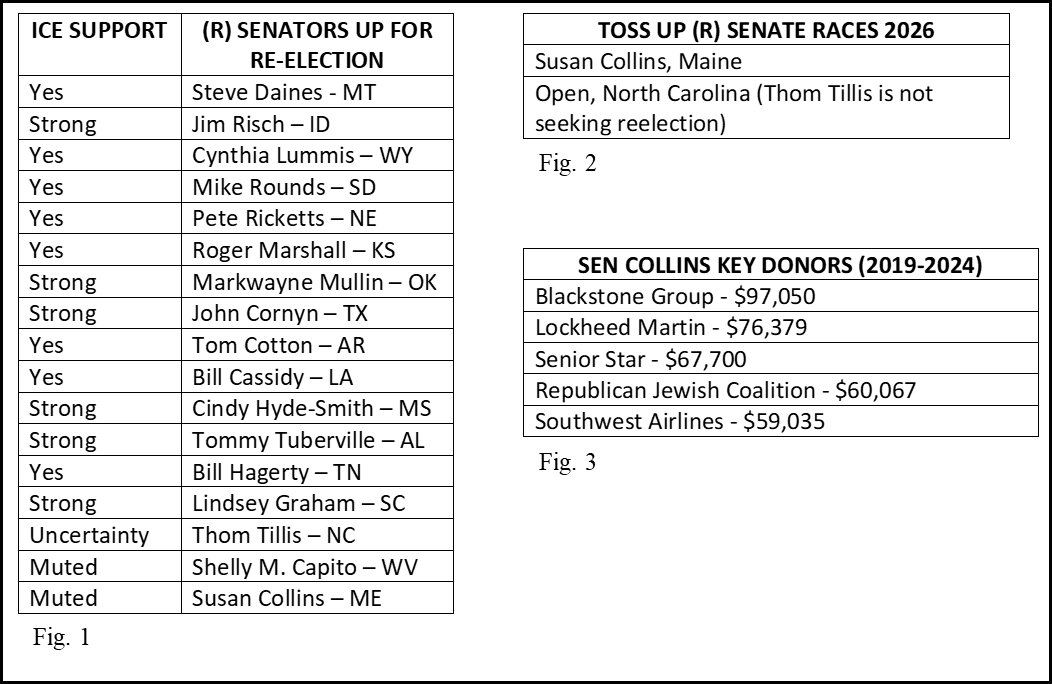

The first step to an effective boycott, the goal of which in this case would be to rein in ICE, is to identify influenceable controllers of the target. While the executive branch is uninfluenceable when it comes to the power of the average American, the same is not true of Congress. There are many politicians who are vocal supporters of Trump’s DOJ, and ICE in particular. There is also an election on the horizon, and the majority of our politicians rely on corporate dollars to run for office. Through a bit of research, we can create a shortlist of congresspersons that support ICE, and congresspersons that are up for reelection. Let’s specifically consider the Senate. I did a bit of analysis, reading various statements from the following republican senators regarding the border, immigration, and ICE’s recent activities.

Now that we have our list of potential targets (Fig 1), we can determine which are the most malleable on the issue, and which seats are most vulnerable. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sen. Susan Collins appears to be the best target. This was determined by assessing her seat’s vulnerability (or in this case, using analysis from Cook Political Report - Fig 2) with the added context of her statements on ICE and its activities.

Fig. 2 data from https://www.cookpolitical.com/ratings/senate-race-rating.

Fig. 3 data from Open Secrets, https://www.opensecrets.org/members-of-congress/susan-collins/summary?cid=N00000491

In looking at her key donors (Fig. 3), the ideal targets for boycott are Senior Star, an assisted living company, and Southwest Airlines. Naturally, Southwest is the reasonable selection for boycott as there are multiple alternatives for consumers, as opposed to asking people to divest from Senior Star or relocate. The boycott and its aim would be rather straightforward. Encourage all liberals, leftists, and faith groups to boycott Southwest Airlines until they cease all political donations going to Sen. Collins due to her support of ICE. Conveniently, we can also easily find that Southwest also donated large sums to Ted Cruz, Sam Graves, and most of all to Donald Trump. The boycott rhetoric could shift in response – Liberals/Leftists/Faith Groups are to boycott Southwest Airlines until they cease donations to politicians who support ICE’s activities.

Recommendations

Of course, having one Senator cease their support of ICE isn’t enough to change the status quo. Research and targeted boycotts would need to continue until enough politicians have flipped, forcing congressional oversight of ICE. To make this method of protest more effective, key policies need to be set in place.

(1) Boycotts should not be made against more than one company in a particular industry at a time. This is to limit disinterest in the protest from potential participants, as well as to promote ease of access. It also permits the protest to last longer, as consumers have alternatives for their needs to be met.

(2) Boycotts must not negatively impact the least fortunate in our society. This strategy is effective because it maximizes our financial power as a whole. Without effective consideration of those with less options or financial power, we lose their financial backing to boycott. For example, a shopping boycott of Walmart would be ineffective, as Walmart serves as the key distributor of necessary goods to many marginalized communities, with little to no alternatives available.

Such protests cannot be done effectively without the participation of thousands of Americans, which requires community leaders to mobilize. The boycotts must be a joint effort, otherwise the financial impact will be limited as it has been in the past. The formation of a council or coalition is a necessity. Bringing together a group of individuals with intersecting needs and concerns, and in turn creating a diverse and powerful boycotting group. My inclination would be rather than creating this from scratch, having organizations that already exist unite and work together to make this a reality.

Final Thoughts

In the future I will continue this line of thought by delving more acutely into the financial power of certain communities that can be leveraged for activism. For the moment, I would simply encourage community organizers to consider my thoughts on the matter, and the ways in which they can maximize their impact by working together. The groundwork is already there. A bit of analysis and collaboration can maximize impact, allowing for more favorable outcomes.

Response to Open Letter on the Israel-Gaza Conflict

By Eli Ibanga

A few weeks ago I wrote an open letter to my congresspersons https://www.elietal.com/insights/open-letter-to-the-virginia-congressional-delegation-regarding-the-israel-gaza-conflict asking for either their support in ending IDF cruelty against Palestinian citizens or an explanation that justifies the current US stance on the conflict. Although I have not received a response from Rep. Beyer, I have received responses from both Senator Tim Kaine, and Senator Mark Warner. My perspective is that Senator Kaine’s letter toed the line of the average US politician and media outlets, framing the suffering of the Palestinians as a consequence of Hamas’ violence. I was very surprised with Senator Warner’s response however, as there appears to be genuine concern for Palestinian safety and their right to self-determination. He supports the two-state solution, and was also cognizant of steps Israel has taken to harm Palestinians, seize their territory, and stymie their push for statehood.

Regardless of my personal beliefs and opinions in regards to the responses received, I would like to thank both Senators and their offices for taking the time to respond to my letter so thoroughly. I have shared both responses below for transparency. I would encourage others with concerns to contact their representatives as well.

(Response from Senator Warner, received 3 June 2025)

Dear Mr. Ibanga,

I appreciate the time you have taken to contact me regarding the situation in Gaza. I remain deeply concerned by the plight of the remaining hostages brutally kidnapped by Hamas terrorists as well as the humanitarian conditions for Palestinian civilians in Gaza.

I am deeply disappointed by the collapse of the ceasefire agreement that was reached in January. The agreement, while standing, allowed for the release of hostages and prisoners, for greater aid access, and stopped the violence that has been so devastating for Gaza – steps that are dramatically needed after a war that has ripped families apart, worsened extreme hunger conditions, leveled entire communities, and threatened broader regional instability.

As a result of the war, more than two million Palestinians in Gaza are currently in dire need of assistance. Even before the October 7, 2023 terror attacks by Hamas, and subsequent military response by Israel, more than a million Palestinians in Gaza relied on humanitarian aid to meet basic needs. Delays and blockages of aid and assistance, as well as the disruption of clean water supplies, have contributed to a situation where the entire population of Gaza now faces acute food insecurity and waterborne diseases resulting from unsanitary conditions.

Returning to a ceasefire agreement must be the priority for diplomatic efforts. Achieving such solution will require sustained U.S. and international engagement to demand a resumption of these efforts, for the sake of innocent civilians who continue to suffer. Achieving a lasting peace will require confronting security, governance, and humanitarian challenges, and identifying funding streams and strategies for reconstructing a now devastated landscape.

I am glad to see that regional leaders have begun to think through those longer-term solutions, which will be critical in ensuring a rebuilt Gaza that is free from Hamas. The leadership of Hamas continues to state clearly that their goal is the complete annihilation of Israel, the only democracy in the Middle East, refuge for the Jewish people, and longstanding friend and ally to the United States in a very challenging region.

There are serious negotiations that must be had in determining specifics of a solution that enables both Israelis and Palestinians to live safely alongside each other with dignity. I wholly reject, however, unserious and dangerous proposals that do nothing but undermine a path to peace. President Trump’s announcement that the United States would “take over” Gaza, presumably necessitating forcible action by the U.S., is offensive, and reckless beyond reason. I am glad to see partner nations in the Middle East steer away from this harmful suggestion, which is destabilizing and antithetical to a Palestinian state in the region. It is in part due to this serious concern that I opposed the nomination of Mike Huckabee when the Senate considered him for the role of U.S. Ambassador to Israel.

I also remain deeply concerned about threats to stability in the West Bank, including continued instances of extremist violence against Palestinians by Israeli settlers. These attacks, which seek to evict Palestinians from their homes and destroy property, carry the potential to provoke a broader conflict. I had pushed the Biden Administration repeatedly to combat this settler violence and enact increasing rounds of sanctions. I condemn the decision by President Trump to revoke that executive authority and unwind the sanctions tied to instability in the West Bank – actions that seemingly give a ‘green light’ to this settler violence.

In discussing the situation in Gaza, let us be clear – Hamas terrorists do not represent the interests of innocent Palestinians, who have often suffered under Hamas control. Nor do they reflect Palestinian American or Muslim communities. This conflict has regrettably inflamed both Islamophobia and anti-Semitism and we must call out acts of violence and hate speech wherever, whenever and however they occur.

I appreciate the time you have taken to share your views with me, and as Vice Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, you may be assured that I will continue to press the Trump Administration, and continue close engagement with our intelligence community and our international allies and partners.

Sincerely,

MARK R. WARNER

United States Senator

(Response from Senator Kaine)

June 9, 2025

Dear Mr. Ibanga:

Thank you for writing to me about the painful events in Gaza, the West Bank, and Israel, initiated by the horrific October 7 Hamas terrorist attack on Israeli civilians. I appreciate hearing from you during this difficult time and join you in grieving the loss of innocent lives.

I have consistently called on Hamas to release all hostages taken in the October 7 terrorist attack. I support the right of Israel to defend itself from Hamas and any other actor – particularly Hezbollah and Iran – who advocates for its destruction. I have consistently and publicly asserted Israel’s right to defend itself from the perpetrators of the October 7 terrorist attacks in a manner that minimizes harm to Palestinian civilians living in Gaza and the West Bank who are themselves victims of Hamas.

The United States should provide support for Israel’s self-defense. At the same time, as a democracy, an ally of the U.S., and a major recipient of U.S. security assistance, Israel must follow international law – as well as U.S. law governing the use of transferred weapons – by providing robust humanitarian support for Palestinians displaced by this war and endeavoring to minimize any harm to innocent civilians. The U.S. and other friends of Israel must contribute to such humanitarian support and press Israel to allow for full humanitarian access in Gaza.

I remain steadfast in my support for Israel’s self-defense, as well as in my belief that the continued transfer of offensive weapons to Israel risks serious harm to civilians in Gaza. Such offensive weapons transfers only further fuel the growing instability in the region and do not contribute to the defense of the Israeli people. That is why on November 20, I voted to oppose the transfers of mortars, tank rounds, and Joint Direct Attack Munitions to Israel by voting yes on the Joint Resolutions of Disapproval introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders.

On July 19, following the Israeli Knesset’s vote to formally reject the establishment of a Palestinian state, I issued a statement that the U.S. should no longer condition recognition of a Palestinian state on Israeli assent, but instead upon Palestinian willingness to peacefully coexist with its neighbors. The world community must engage in a persistent effort to find a path toward what was promised to Israelis and Palestinians 75 years ago: two states living peacefully as neighbors.

Following the events of October 7 and their aftermath, we have seen a deeply distressing spike in antisemitism and Islamophobia here in America. I forcefully reject hatred and bigotry in all forms, and have fought to ensure that places of worship have access to federal resources so all who wish to exercise their faith have the freedom to do so in peace. All Americans should recommit to a society where we can live, work, worship, and educate our children together in a climate of mutual respect, even when we disagree on matters of domestic or foreign policy.

On January 19, after 15 months of horrific conflict, Israel and Hamas began implementing the first phase of a three-phase ceasefire. The first phase includes a complete ceasefire, exchange of 33 Israeli hostages for 1,900 Palestinian prisoners, increased humanitarian assistance into Gaza, and the ability for displaced Palestinians to return to the north. The second phase includes a permanent ceasefire, an exchange of the remaining Israeli hostages for more Palestinian prisoners, and the complete withdrawal of Israeli forces from Gaza. The third and final phase includes the return of all remaining bodies of deceased hostages and the reconstruction of Gaza.

I am grateful for the former Biden Administration’s tireless efforts to negotiate a ceasefire deal – which I had long called for – to reunite hostage families and provide Gaza with desperately-needed humanitarian assistance. This agreement, which the Trump Administration supported, marked an important step towards a durable peace. It is in the best interest of hostage families, the Israeli and Palestinian people, and U.S. civilians and military personnel throughout the region that we continue to build on this progress.

On February 4, President Donald Trump declared that the U.S. should seize control of Gaza and forcibly displace millions of Palestinians, including through the use of military force, to take over Gaza. On February 7, I led my colleagues in introducing a resolution affirming that the Palestinian people have a right to self-determination and rejecting any attempt to deploy U.S. military assets or personnel to Gaza. I believe it is critical to remain committed to the ceasefire process, rather than dragging our servicemembers into another endless war in the Middle East, if there is to be any hope of a peaceful resolution to the crisis.

Based on national security briefings on Capitol Hill, meeting personally with survivors of the October 7 attacks, meeting with families who’ve lost loved ones or have had loved ones taken hostage, hearing from Virginia communities, and simply following the news, it is clear to me that there is much left to do. I will continue to publicly and privately condemn Hamas’ acts of terror against Israelis, advocate for the continued implementation of a permanent ceasefire and de-escalation of tensions across the region, encourage efforts to prevent civilian casualties and return hostages to their families, support the safe and swift delivery of humanitarian assistance to Gaza and the West Bank, and reconstruction efforts in Gaza.

Thank you again for writing to me and for sharing your perspective and concerns.

Open Letter to the Virginia Congressional Delegation Regarding the Israel-Gaza Conflict

Word from Eli Ibanga, Owner, ELIETAL - “I believe that ethics must come first above all else. As such, I’ve written a letter to my representatives: Senator Tim Kaine, Senator Mark Warner, and Representative Don Beyer, addressing concerns I have relating to Israel’s actions in Gaza and their impact on the United States. To maintain transparency and adhere to my values, I’ve decided to publish this letter to the public. I implore all readers to consider contacting their own representatives in regards to this conflict as well.”

Dear Senator Kaine, Senator Warner, and Representative Beyer,

The purpose of this letter is to seek clarification on the reasons for the United States continued support to Israel under the current circumstances of the Gazan conflict. As a former US army officer, as well as a veteran of Operation Resolute Support in Afghanistan, US Citizen, and Virginia resident, I fail to see any ethical reason for almost every US politician to publicly defend Israel and approve continued military support to them when there are documented human rights violations, wanton killing of Palestinian civilians, and the IDF’s blatant disregard for ethics. The actions of the IDF in this conflict are in stark contrast to the standards of behavior we hold of our own military, and our continued alliance with Israel appears unbecoming under these circumstances.

Of all issues relating to the conflict in Gaza, I find Israel’s violations of the Geneva Conventions most concerning. I fear permanent damage has been done to the image and credibility of the United States because of our politicians’ unconditional support of Israel despite the extensive evidence and international condemnation of Israel’s crimes. The Geneva Conventions has several Provisions and Protocols that the US has ratified or at least endorsed as a signatory. Despite not ratifying all protocols, the United States military very closely adheres to all Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols, as well as the Law of War. I expect the United States to only ally with nations that maintain the same high standards of integrity. It is my assumption that Israel has avoided signing or ratifying Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions to allow for military action against Palestinians while being immune to international law. Additional Protocol I governs civilian victims of armed conflicts in which people are fighting against “colonial domination, alien occupation, or racist regimes” (Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Bern, 1978). While Israel is technically not in violation of this as it is not a signatory, these are rules that the United States has endorsed and follows despite not ratifying them. Israel also appears to have breached several articles of the core Geneva Conventions, which it has signed and ratified, via torture and mutilation, taking of hostages, humiliation of hostages, and not caring for the sick and wounded (ICRC, Commentary on the First Geneva Convention, 2016). There is documented evidence of Israel killing civilians (Al-Mughrabi & Farge, 2025). To date, Israel has not taken accountability, nor corrected its operational failures to limit future civilian casualties. The United States military caused a similar number of civilian casualties to the Gazan conflict in Iraq – over a period of eight years, with most civilian casualties coming in the first two years of conflict (Hamourtziadou, 2023). But whereas Israel sees nothing wrong with its actions, the US took measures to limit the number of civilian casualties, and succeeded. We simply cannot insist on unwavering support of Israel and the IDF when they lack the moral fortitude to acknowledge their own wrongdoing. While I understand that Israel is considered a close ally to the United States, I am not aware of any treaties binding us to their defense, especially when it would seem they do not adhere to nor believe in the values we champion as a country.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, despite the cost of American lives, the US military implemented rules of engagement that limited civilian casualties. In 20 years of war, we caused no comparable level of destruction to infrastructure to any city in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Syria to that which Israel has caused in Gaza – excepting Raqqa, where we still took initiative to rebuild through USAID. The destruction of Raqqa does not justify the destruction of Gaza. Even more damming, we have US Soldiers jailed for violations of the Law of War and Geneva Conventions from our conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, several US Soldiers were court martialed and jailed for the killing of unarmed civilians, and their subsequent attempts to frame said citizens as combatants (BBC, 2011). From the Iraq War, Soldiers were court martialed for their torture of detainees (Barakat, 2024). Comparatively, Israel has been accused of the torture of detainees many times during its current military campaign in Gaza (United Nations, 2024). Israel has also been accused of wanton killing of civilians, with many instances of evidence flooding the internet daily for the past year and a half. Israel has again found itself guilty of no wrongdoing – despite the claims of international scholars, the United Nations, and even former Israel Prime Minister Olmert (Tondo, 2025). If we are willing to hold our own Soldiers to account, we must have the moral fiber to hold an ally to requisite standards. While I understand Israel is our ally and not our subordinate, we can certainly refuse to enable or endorse their amoral behavior. The IDF has consistently violated internationally recognized standards of warfare that the nation of Israel has agreed to. There is documented evidence of them targeting hospitals, attacking civilians, enabling famine, killing journalists, and even killing UN personnel, all while absolving themselves of guilt (Rubenstein & Morrison, 2024; Committee to Protect Journalists, 2025; El Deeb, 2025; Lazzarini, 2025). If the US turns a blind eye to the slaughter of civilians and other such crimes we will capitulate our moral leadership role globally, increasing the risk to Americans and American interests.

My hope is that my assessment here is incorrect due to some glaring oversight on my part. I would implore you not to give me, nor the American public, anecdotes regarding Hamas’ violence towards Israel as justification for Israel’s actions. Hamas is a terrorist organization. We should hold ourselves and our allies to higher standards of behavior than such a group. If there is classified information that justifies this behavior, then I would request the US government declassify it and share it with the public in order to repair our damaged reputation and ignite our collective belief in this cause. I hope my concerns stem from a misunderstanding, and welcome a response from you that address these concerns or indicates a renewed commitment to principled foreign policy and holding our allies to the same standards that we expect of ourselves.

Very respectfully,

Elisha Ibanga

Resident of Arlington, Virginia

References

Al-Mughrabi , N., & Farge, E. (2025, March 24). Gaza death toll: How many Palestinians has Israel’s offensive killed?. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/how-many-palestinians-has-israels-gaza-offensive-killed-2025-01-15/

Barakat, M. (2024, April 12). 20 years later, Abu Ghraib detainees get their day in US court. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/abu-ghraib-lawsuit-caci-virginia-contractor-torture-47bca65df10c62b672944692a139e012

BBC. (2011, March 24). Jeremy Morlock jailed for 24 years over Afghan deaths. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-12836851

Committee to Protect Journalists (2025, 28 May). Journalist casualties in the Israel-gaza war. https://cpj.org/2023/10/journalist-casualties-in-the-israel-gaza-conflict/

El Deeb, S. (2025, May 19). Aid workers feel helpless as Israel’s blockade pushes Gaza towards famine. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/gaza-israel-palestinians-war-aid-blockade-12e18ac4b6d9fbdd1f058c7fcec4c97c

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Bern (1978). Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977.). International Humanitarian Law. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/api-1977

Hamourtziadou, L. (2023, March 20). How many Iraqis did the US really kill?. Asia Times. https://asiatimes.com/2023/03/how-many-iraqis-did-the-us-really-kill/#

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Commentary on the First Geneva Convention: Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, 2nd edition, 2016. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/full/GCI-commentary

Lazzarini, P. (2025, May 28). UNRWA commissioner-general on Gaza: A summary execution among more than 310 UNRWA staff killed in Gaza | unrwa. https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/official-statements/unrwa-commissioner-general-gaza-summary-execution-among-more-310-unrwa

Rubenstein, L. S., & Morrison, J. S. (2024, March 24). Facts and falsehoods: Israel’s attacks against Gaza’s Hospitals. Think Global Health. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/facts-and-falsehoods-israels-attacks-against-gazas-hospitals

Tondo, L. (2025, May 27). Former Israeli PM Ehud Olmert says his country is committing war crimes. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/may/27/former-israeli-pm-ehud-olmert-says-his-country-is-committing-war-crimes

United Nations (2024, August 5). Israel’s escalating use of torture against Palestinians in custody a preventable crime against humanity: UN experts | ohchr. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Chancellor. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/08/israels-escalating-use-torture-against-palestinians-custody-preventable

The Environmental Cost of AI

By Eli Ibanga

Edited By Victoria Sosa

A few years ago, I was a panelist for a discussion on the benefits of utilizing AI in support of emergency management operations. I proposed that AI could be used for analyzing financial and location data to better anticipate community needs in advance of natural disasters. While I don’t regret that take, I do think our collective jets should be cooled on AI. Within the last few years, there has been a noticeable push across industries to develop and implement AI, with key goals appearing to be an automation of tasks to decrease costs whilst developing new revenue streams for companies involved in the development and deployment of AI tools. Furthermore, the technology has become part of the average tech layman’s toolbox, with tools like ChatGPT being used across the world daily. While AI undoubtedly has immense potential for good, I believe it is currently being used irresponsibly, partly due to little oversight and regulation. There’s a myriad of potential issues such as biases in the training of algorithms, unethical AI deployment, and its sociological impact, but in the spirit of Earth Month I’d like to focus on the carbon footprint of AI.

I found statistics on AI tools’ climate impact were both underwhelming and jarring, depending on the context through which I considered the data. On one hand, AI’s energy consumption is only approximately 3% of Earth’s total emissions (Kemene et al., 2024). However, the typical ChatGPT inquiry uses approximately 10 times the energy used by a traditional digital inquiry method, like a Google search (Parshall, 2024). Generative AI uses around 33 times more energy to complete a task than “task specific” software (Kemene et al., 2024). Those figures are large, but they mean next to nothing without contextualization. For this, let us take a closer look at what is probably the most famous AI tool at the moment, ChatGPT.

ChatGPT produces around 4.32 grams of carbon dioxide per query, and receives around 50 million unique visits each day (Mittal, 2024). This works out to nearly 78,840 metric tons of CO2 production annually. Compared to the USA, that’s a drop in the bucket, as we generate nearly 18 million metric tons of CO2 per day (EPA, 2024). But what about the amount of power used? Many environmental activists and researchers have begun to realize that some “green” products may have a negative cumulative effect on the climate crisis. If an electric car is developed, or a wind turbine installed, we all feel good because it’s an environmentally conscious product. But what of the environmental cost? Is the supply chain environmentally sound? Are the net emissions to create and sustain such an item worth it? What is the human cost to produce these products? These are the questions we must consider when looking at emerging technologies to better assess their net impact on the environment.

Let’s examine ChatGPT’s climate impact by comparing its energy consumption and emissions to a country like Pakistan, a notable developing country with a large population. Pakistan ranks 5th for largest population worldwide, 32nd for CO2 emissions, and 26th for electricity consumption when compared to other countries and territories (Crippa, et al., 2024; Fulghum, 2024; United Nations, 2024). As ChatGPT is essentially a digital application, we can ignore supply chain emissions, as those are more attributable to smartphone and computer developers (just in case you are wondering though, there are a LOT of emissions there). ChatGPT generates 7.62 metric tons of CO2 in a year, compared to Pakistan’s annual CO2 emissions of 200.51 teragrams (Crippa, et al., 2024; Mittal, 2024). This pales even further when compared to a country like the USA’s 4,682.04 teragrams worth of CO2 emissions (Crippa, et al., 2024).

So, we’ve established that when compared to the biggest of polluters, AI is nowhere close to being one of the main culprits, but that’s only when considering CO2 emissions. ChatGPT annually uses 14.46B kWh, or 8.45% of the electricity that Pakistan uses over the same period, which is made more disturbing when we consider that Pakistan has the 5th largest population worldwide (Fulghum, 2024; United Nations, 2024; Wright 2025). It’s even more scary when you consider that the AI tool uses an equivalent amount of water per month to that of every person on Earth having two glasses of water (Wright, 2025).

Looking at some hopefully more digestible figures, when you drive just one mile in an average gasoline-powered vehicle you produce CO2 emissions equivalent to generating about 243 AI images (Heikkilä, 2023). Despite this, the AI tool could use approximately the same amount of electricity as it takes to charge your smartphone to generate just one of those images (Heikkilä, 2023). Within that context, the use of AI for trivial tasks seems irresponsible at best and unethical at worst (looking at you, AI photo enthusiasts). On a small scale, the aimless ChatGPT query is a drop in a bucket. But cumulative impact paints a grimmer picture.

So, it's clear that using AI won't send the Earth to a fiery grave, at least not on its own, but if AI remains unregulated then the public will remain uninformed on its true environmental impact. This ignorance could erode the very small gains the global community has made against climate change. When considering the environmental cost of AI, one should consider both the energy usage (how much energy will it use, and what else could that energy be used for) as well as its greenhouse emissions (what is the negative impact on the planet). Humanity has introduced a new energy consumption and emissions variable in AI, and it wasn’t created with the purpose of replacing a less sustainable system either. The disconnect between AI’s negative impact on our planet and its potential to aid our everyday lives must be rectified to guarantee that while the AI sector continues to grow, we prioritize Earth’s sustainability over convenience and profitability.

References:

Blue, M.-L. (2022, August 30). What is the carbon footprint of a plastic bottle?. Sciencing. https://www.sciencing.com/carbon-footprint-plastic-bottle-12307187/

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025, January). Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

Crippa, M., Guizzardi, D., Pagani, F., Banja, M., Muntean, M., Schaaf, E., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Becker, W., Quadrelli, R., Risquez Martin, A., Taghavi-Moharamli, P., Köykkä, J., Grassi, G., Rossi, S., Melo, J., Oom, D., Branco, A., San-Miguel, J., Manca, G., Pisoni, E., Vignati, E. and Pekar, F., GHG emissions of all world countries, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2024, doi:10.2760/4002897, JRC138862

Edwards, C., & Fry, J. M. (2011, July 25). Life cycle assessment of supermarket carrierbags: A review of the bags available in 2006. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/life-cycle-assessment-of-supermarket-carrierbags-a-review-of-the-bags-available-in-2006

Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, January). What If More People Bought Groceries Online Instead of Driving to a Store?. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/what-if-more-people-bought-groceries-online-instead-driving-store#:~:text=What’s%20the%20big%20deal?,times%20the%20distance%20to%20Pluto!&text=All%20these%20car%20trips%20result,out%20of%20milk%20again.%E2%80%9D)

Environmental Protection Agency. (2024, April 11). Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2022 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 430R-24004. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks-1990-2022.

EUROCONTROL Business Cases (2024, June 18). Standard Inputs for Economic Analyses. EUROCONTROL. (10) 7-7.5. https://ansperformance.eu/economics/cba/standard-inputs/chapters/amount_of_emissions_released_by_fuel_burn.html

Fulghum, N. (2024, December 9). Yearly Electricity Data. Ember. https://ember-energy.org/data/yearly-electricity-data/

Heikkilä, M. (2023, December 1). Making an image with generative AI uses as much energy as charging your phone. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/12/01/1084189/making-an-image-with-generative-ai-uses-as-much-energy-as-charging-your-phone/

Kemene, E., Valkhof, B., & Tladi, T. (2024, July 22). AI and energy: Will AI reduce emissions or increase demand?. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/07/generative-ai-energy-emissions/#:~:text=How%20much%20energy%20does%20AI,just%20users%20on%20one%20platform.&text=How%20can%20business%20leaders%20strike,of%20the%20Annual%20Meeting%202025

Mittal, A. (2024, October 8). CHATGPT: How much does each query contribute to carbon emissions?. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/chatgpt-how-much-does-each-query-contribute-carbon-emissions-mittal-wjf8c/

Parshall, A. (2024, June 13). What do Google’s AI answers cost the environment? Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-do-googles-ai-answers-cost-the-environment/

Pearce, C. (2023, July 12). How many cars equal the CO2 emissions of one plane?. BBC Science Focus Magazine. https://www.sciencefocus.com/future-technology/how-many-cars-equal-the-co2-emissions-of-one-plane

United Nations (2024). World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2024/TR/NO. 9. New York: United Nations.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2023, June). Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=97&t=3

Wright, I. (2025, March 6). ChatGPT energy consumption visualized - beuk. Business Energy UK. https://www.businessenergyuk.com/knowledge-hub/chatgpt-energy-consumption-visualized/

Greed Ruined the NFT - And Why Fortnite Can Save It

By Eli Ibanga

During the height of the COVID-19 global pandemic just about everyone had heard of NFTs, and many companies were hard at work trying to find ways to extract value from technology without doing their due diligence. Notable brands found themselves in a race to extract value and profit from this “hot” technology, and in the pursuit of greed they found themselves putting the cart before the horse.

First, let’s tackle the technology. An NFT is essentially a digital receipt. This “receipt” has an unchangeable ledger that can be viewed online (the blockchain), which of course demonstrates proof of ownership (Sharma, 2024). Thus, it makes sense that the perceived value of NFTs is in the exclusivity of owning one. One will always be able to trace NFT transactions back to the blockchain, thus proof of ownership is absolute. When compared to some more traditional sales venues NFT transactions also have less intermediaries (Sharma, 2024). They cannot be imitated or copied – except for when they are.

In popular mockery of the technology, detractors would copy the NFTs using screenshots, then post the image to ridicule the NFT owner. This mockery of course offended many NFT owners, but there was no recourse available to them. The court of public opinion found NFTs to be a stupid idea. Furthermore, our governments have proven themselves slow to enact laws to regulate emerging technologies, especially when that tech is exclusively used on the internet. AI is the most popular boogeyman on this front (West, 2024). Compounding the problem was the fact that a lot of the NFT art (and I use that term very loosely) was stolen from actual artist, or had ridiculous origins (Collier, 2022). Tascha-Labs literally took a picture of a diamond, then destroyed it and minted the photo to the blockchain (Tascha-Labs, 2021). All these actions were taken in an effort to create value for the NFT through artificial scarcity. Although NFTs are digitally unique, they are inherently worthless. Thus, a reason needs to be created to give someone a reason to purchase one. But a picture of a diamond? Ugly monkey gifs? Is that really the best we are capable of? The issue with NFTs, as stated in the beginning of this piece, is that the cart was put before the horse. The ideal use of an NFT is to add value to an already popular service through exclusivity. Tascha’s Destroyed Diamond was…well, destroyed, because owning the NFT was worthless so long as the actual diamond existed. Bored-Ape-Yacht-Clubs monkeys were stupid because they became over-saturated before there was any reason to want to actually be a member of the club. What is crazy about all of this is that there was an ideal use case for NFTs all along – and that is Fortnite. Yes, the free-to-play video game.

Fortnite offers its service free to players on various gaming platforms, thus having maximum accessibility options for users. They generate actual revenue through the selling of in game cosmetics, such as skins, music, and emotes (Ganti, 2020). These cosmetics give no advantage to the purchaser, unlike microtransactions in the majority of other games. They strictly exist to allow the owner to express a more unique personality. Fortnite limits access to these items in two ways. The first, of course, is to charge for these items. The second is by creating artificial scarcity by limiting purchasing availability to these items, meaning if you don’t get it when its available you have no idea when you will be able to get it again. Every time I play Fortnite I am disappointed that I never got the opportunity to get the “Verve” emote myself.

By using stringent rules regarding cheating and account security, Fortnite has successfully created the “meta-verse” that so many other companies have aspired, and failed, to create. Players aren’t even always in the game to earn that elusive Victory Royale. There are social events and brand collaborations, such as one with Shuiesha and Toei Animation, that allowed players to watch episodes of Dragon Ball Super in-game while hanging out with friends (The Fortnite Team, 2022). This of course coincided with a limited release of Dragon Ball themed emotes and skins. So Fortnite offers: (1) an established metaverse with its own draw for users to want to participate, (2) a robust user-base that motivates companies to want to advertise and collaborate on their platform, and (3) purchasable exclusive cosmetics that provide no benefit to players beyond them being able to express their personality in a unique manner. And this formula has been a roaring success. In fact, it’s so successful that there is an “illegal” (against Fortnite terms of service) market for selling Fortnite accounts with rare cosmetics to other players!

In closing, I think it is clear that companies trying to leverage NFTs for new streams of revenue need not give up their aspirations, but refocus them. The aim should be to actually provide something of value to the consumer, not simply to get in front of the pack in the race to make money. Of course, even Epic Games (the developer of Fortnite) is not immune to errors on this front, with it allowing many “crypto-games” of varying quality and repute on its store. And to be fair, this only half-covers the topic as it is difficult to touch on NFTs and the blockchain without delving into cryptocurrencies. But I think we shall save that discussion for a part 2.

References:

Collier, K. (2022, January 10). NFT Art sales are booming. just without some artists’ permission. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/security/nft-art-sales-are-booming-just-artists-permission-rcna10798

The Fortnite Team. (2022, August 16). Your power is unleashed! Goku powers up fortnite X dragon ball. Fortnite News. https://www.fortnite.com/news/goku-powers-up-fortnite-x-dragon-ball-your-power-is-unleashed

Ganti, A. (2020, September 10). How does fortnite make money?. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/tech/how-does-fortnite-make-money/

Sharma, R. (2024, June 12). Non-fungible token (NFT): What it means and how it works. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/non-fungible-tokens-nft-5115211

Tascha-Labs. (2021, September). Tascha’s Destroyed Diamond. Retrieved March 19, 2025, from https://opensea.io/assets/ethereum/0x2a9e4045185c8d778b85610ca96d79bd8ecdc720/1.

West, D. M., Wheeler, T., Sorelle Friedler, S. V., MacCarthy, M., & Nicol Turner Lee, T. W. (2024, October 10). The three challenges of AI Regulation. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-three-challenges-of-ai-regulation/